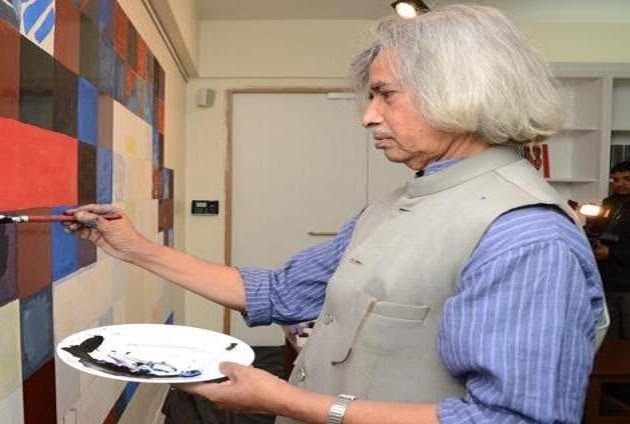

Jogen Chowdhury stands among India’s best known living painters. He works in a way that keeps old Indian marks and stories alive while using them in new pictures that people outside India also read with ease. He draws a steady, wiry line, sets down flat but strong shapes and loads each image with clear signs – eyes, birds, snakes, slippers – so the picture feels private to him and open to everyone at the same moment. The pictures look old – yet they surprise. He started with village memories besides Calcutta walls and he still feeds those memories into new colours and sizes. The lesson is plain – if an artist keeps hold of the ground where he first stood, he can move far without slipping.

Early Influences: The Foundation of Tradition

Jogen Chowdhury was born in 1939 in Faridpur, a town that now lies in Bangladesh. As a child he lived among Bengal’s country people, saw their harvest fairs, watched potters shape clay and joined village festivals where painted scrolls and paper masks filled the night. Those sights and sounds taught him how a picture can speak like a song.

After the partition of 1947, his family crossed the new border and settled in Calcutta. jogen chowdhury enrolled at the Government College of Art & Craft. The teachers there still followed the Bengal School, a group that had turned away from oily European realism but also looked instead at old Indian miniatures, village textiles and epic scrolls. The lessons of that school stayed inside him and later ran through every line he drew.

The Paris Influence: Embracing Modernity

A key shift in Chowdhury’s growth happened while he studied at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris from 1965 – 1970. He lived inside the European avant garde scene and faced modernist tests that broke old rules. Direct contact with Western art waves – mainly surrealism, expressionism and cubism – broadened his grasp of shape and abstraction.

Chowdhury did not copy Western modernism – he took it in – used its tools to voice his own Indian views. The blend created a clear visual speech – fixed in Indian life – yet ready for world wide ideas.

The Power of the Line: Tradition Reimagined

A plain look at Jogen Chowdhury’s pictures shows that the first thing to notice is the way he handles a single stroke. The curves bend and turn without a break and the bodies he draws look alive because those curves stay in motion. The stroke is not a frame that keeps colour inside – it acts as nerves and muscles tightening or slackening to say what the sitter feels inside.

The same kind of stroke appears in older Bengali pictures. Kalighat street painters and village scroll singers told long tales with only a few quick marks. Chowdhury borrows that spare vocabulary and pushes it into the present – he pulls a limb longer, swells a belly wider, repeats a curl until it beats like a drum. The bodies he gives us look elegant and deformed at once, fair and foul in the same breath – they lay bare the clash that lives in every person.

The Human Form: A Dialogue Between Past and Present

Jogen Chowdhury puts the human body at the center of every canvas. The flesh he paints is warm, alive and heavy with meaning. Arms and legs swell to unlikely lengths, eyes push forward like smooth stones and every patch of skin carries marks that look like old scars or new worries. In this way he takes the old Indian idea that the body holds spirit and morals and gives it a fresh twist.

The people on his canvas never appear as perfect gods or storybook heroes – they look like the man who sells vegetables down the lane or the woman who waits at the bus stop. Each one freezes for a second in which hunger, shame or a bitter joke crosses the face. By showing that moment Chowdhury speaks of the India that grew after 1947: cities that sprout concrete towers while old rules still whisper in every home, money that divides neighbor from neighbor and love affairs that crack under small daily pressures.

With plain paint he turns old Indian figure studies into pictures of the mind – he keeps the color, curve and shine of traditional art – yet he asks hard questions about the way we live now.

Color, Texture, and Symbolism

Chowdhury keeps most colours quiet – yet each shade carries clear meaning. Reds and ochres fill the canvas – they match the soil of Bengal and the dyes of local cloth. The hues plant the painting firmly in Indian ground and still look fresh to any eye.

Texture matters as much as colour – he criss crosses lines and builds tight repeats until the skin of each figure feels solid, like carved wood. The method mirrors rough cotton saris but also ancient stone reliefs – yet he pushes it until it speaks of present day feeling rather than old decoration.

By setting shape colour and surface against one another, Chowdhury sets up a plain conversation – what the eye can touch versus what lies beyond reach and how a body hides the very mood it carries.

The Subtle Satire in His Works

Jogen Chowdhury slips quiet mockery into his pictures. The people look handsome at first glance – yet a dry joke runs through them. Their posed hands and sly faces copy the double dealing that fills present day life.

He keeps alive the old Bengali habit of poking fun through pictures, the same habit that once filled Kalighat street paintings with jokes against folly. Chowdhury smooths the joke and moves it inward – he paints the tug-of-war inside a person rather than loud public ridicule. He watches men and women caught between old custom and new demand and he sets that strain on the canvas.

The Role of Symbolism and Myth

Chowdhury paints modern life – yet he stitches old Indian stories into the pictures. Again and again he draws the same things – a snake, a fish, a blossom, an eye. Each thing holds more than one plain meaning.

The snake does not just lie there – it whispers of risk or of wanting. The fish is not only food – it hints at new birth or at being caught. The flower and the eye carry their own double messages. When those old signs sit inside a city scene, they let the viewer feel at home with yesterday while looking at this day. Chowdhury builds a small dictionary of pictures that speaks first to Indians and then to anyone willing to listen.

Jogen Chowdhury and His Impact on Indian Contemporary Art

Jogen Chowdhury built a firm place in Indian contemporary art by mixing old and familiar motifs with fresh, personal ways of drawing and painting. Young artists who watch him learn that they do not have to choose between knowing who they are and trying something new – they keep the past alive by changing it, not by throwing it away.

Paintings and drawings by Chowdhury now hang in well known museums and galleries on multiple continents. ArtAliveGallery, a leading Indian platform for new art, has staged many of those exhibitions. The gallery sets the pictures in clear light, writes plain labels and invites viewers to come close – the quiet details and private stories in each work become easy to see and feel.

Legacy of Balance: Tradition as Foundation, Modernity as Vision

Indian art keeps shifting, but Jogen Chowdhury holds steady and still moves forward. He sticks to the culture he grew up with – yet people anywhere understand his pictures. He keeps the old Indian way of seeing things and adds strong, up-to-date feeling that belongs to no single place or decade.

In his paintings tradition and new ways stand side by side instead of fighting. The past stays alive because he paints it again with bright color, clear line but also open feeling. People who look at the pictures feel more than praise – they think about how to feel both new besides Indian at the same moment.